Identity-First vs. Person-First Language and the Case for Inclusivity

Out of a number of communication methods available to us - spoken language, written language, gestures, body and facial expressions, sounds, movement, gifs, memes, emojis, etc. - language in the form of words is one we continuously add to, remove from and perfect in order to try to describe and encompass the human experience.

Language has evolved significantly from the time we began communicating as a species, and it continues to change as we collectively examine and re-examine what is appropriate, what is taboo and what is still nebulous.

When it comes to describing identity many people use language with the goal of being polite rather that with the goal of being inclusive.

How many of us follow language trends simply because we heard others’ rules about what is proper and what is rude, without ever examining why or what alternatives exist?

How do we move from our desire to be “nice” toward being advocates for better language, better access and even a better world?

In this blog we will dive further into the two types of language used when it comes to identity, discuss why it matters and make a case for choosing one over the other.

Identity and language: person-first or identity-first?

I remember overhearing a conversation between two people where one speaker used the words “disabled person” and the other’s response was “You know, we don’t say that anymore, it’s kind of rude. It’s better to say ‘a person with a disability instead.’”

You may have heard the same adage: saying person with X is better than saying X person. But have you ever wondered why?

Before we go any further, let’s quickly review the two types of language used in relation to identity and their basic premises.

When it comes to how we describe someone, we tend to choose either person-first language or identity-first language.

For example we may say:

person with autism (person-first language) vs. autistic person (identity-first language)

person with a disability (person-first language) vs. disabled person (identity-first language)

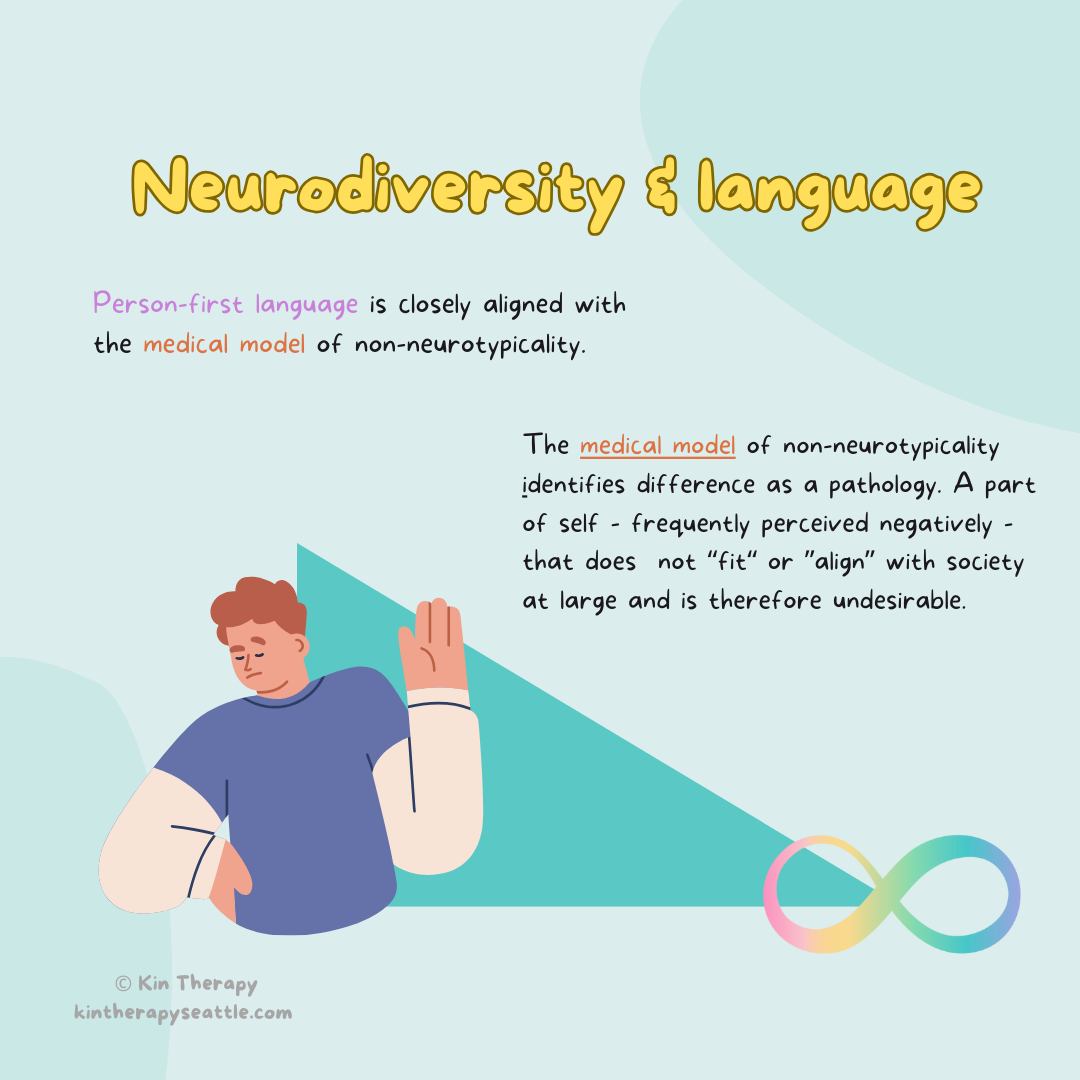

Person-first language aims to separate the person from their “illness” or “disorder” and claims people are not defined by their disabilities.

Identity-first language claims identity in disability and acknowledges they are inseparable. It takes pride in the identity marker and acknowledges that one’s sense of self as well as their interactions with others and the world are framed through identity.

Person-first language

Many who use person-first language will argue that this form of referring to people rightfully puts the person first and their disability second. It is not uncommon to hear others say that people are “more than their disabilities”. You have likely heard that using anything but person-first language is disrespectful and rude, and that the goal is to focus on a person’s worth beyond their disability. Another common phrase is that people shouldn’t define themselves by their disability.

But few stop to wonder - why is it implied that having a disability diminishes a human’s worth? Why is disability framed as something to overcome, to rise above?

The answer to this, as I see it, comes down to what our society and systems view as the “norm”, the “typical” and the desirable.

In a society that values white, straight, male, cishet bodies above all others, a body that is disabled is viewed as an aberration. It is also presumed that everyone would want to be the norm, making anything that is different an inconvenience at best, and a stain to be removed at worst (this is where the drive for the “norm” takes a dark turn towards eugenics, forced sterilization and other atrocities).

When we say “person with a disability”, we (in most cases) unknowingly frame disability as something negative and undesirable, akin to a disease or an illness that one would surely want to be rid of or overcome. In these instances we are perpetuating the bias that we have internalized from the systems of oppression we live under that force us to be or constantly move toward that “norm”.

We have internalized the assumption that disability is bad, unwanted and unwelcome and that no one wants to be disabled, therefore the kind and polite thing to do is to put distance between the person and their disability. Put the person first, because disability is equated with disease, shame and inconvenience, something to look away from or to relegate to the shadows.

Identity-first language

Language is personal and is intricately tied to our identity.

Language is also political. In the case of person-first language, we may unwittingly choose to perpetuate the harm created and caused by the systems around us against people who are marginalized in any capacity, who are not deemed to be a part of the “norm”.

Using identity-first language acknowledges how intrinsic something is to us, inseparable from who we are as a human and how we interact with the world.

The components that mark our identity - gender, race, socioeconomic status, age, body size, sexuality, neurodivergence, mental health, etc. - determine our proximity to power. They can give us unearned privileges and help us pass through doorways people with other identities may be barricaded from. Or they can prevent us from gaining access to services, people or places others may have no difficulty getting.

Putting identity first acknowledges it is an inherent part of our “self” and it also dictates how we interact with and access the world at large.

An autistic person, for example, is always going to be autistic - whether they are at the doctor’s office or at a party.

Their autism is not a switch that can be turned on and off for convenience. Each setting will be interacted with and viewed through the lens of their identity: at the doctor’s office it may be wondering whether they will be taken seriously during their appointment, noticing the brightness of the lights in the waiting room or being acutely aware of the noises coming from the people they are sitting next to. All these stimuli will be taken in, processed and reacted to through the lens of their autism.

If it’s at a party, social interactions with others will also be informed by this person’s autistic identity. What they say, how they communicate, their body language and facial expressions will be perceived and reacted to by others, who may form opinions or judgements of this person based on these variables.

The person in this example cannot take autism out of their identity, put it on a metaphorical shelf and say, “You know, I don’t feel like being autistic today so I will leave this part of me at home. Today I will be “normal”, just like everyone else.”

Their autism is as much a part of them as their nose. They can’t remove it when they don’t feel like using their sense of smell.

Moreover, even if said person wanted to forget about this identity marker for an hour or a day, the world is unlikely to let them. While out and about, they will inevitably notice the components of everyday life that are created and catered to the “norm”, from architecture and design, to restaurant menus and places of employment.

It is impossible to live in this world and not to interact with it through your identity, especially when this world is not build for the identity markers you hold.

Inclusivity, social justice and pride

Encyclopedia Britannica defines social justice as "the fair treatment and equitable status of all individuals and social groups within a state or society."

Yet we already know that in our society not all individuals or groups of people are treated fairly or equally. Going back to what we talked about above in reference to the “norm”, those who fall outside of it are generally treated with significantly less consideration, fairness and dignity.

Those outside the “norm” are routinely other-ed, receiving the message that whatever identity marks them as outsiders is undesirable and is best hidden or removed.

Embracing these other-ed identities and expressing pride in them is an act of social justice. It is taking up space where we may be told to hide. It is advocacy for ourselves and others, saying that being outside the “norm” is not a mistake, a sin or a failure. It is demanding equal access to services, goods, people and places that those who are deemed the “norm” receive easily.

When we highlight pride, talent or trait integral to ourselves, we use identity-first language: Black person instead of person with Blackness. Gay person instead of person with gayness. Woman instead of person with womanness, and so on. We allow these key identity pieces to integrate into the whole of our selves, rather than leaving them consigned to the margins, fragmented and far away from our entire being.

Ultimately, every individual has the right to choose for themselves how they speak about themselves, whether they use identity-first or person-first language.

However when it comes to referring to the identities of others I urge you to consider your own positionality, your relationship with power, your intentions and potential impact of your words on someone else.

As we all work toward a more inclusive, accessible and accepting world, let us practice awareness and intentionality with each other. Let’s strive to move beyond being “nice” or “polite”, choosing to ask the hard questions and to practice advocacy instead.